Len Bias: The Supernova of 1986

In 1986, the Boston Celtics drafted one of the most promising basketball stars, alongside the likes of Michael Jordan.

In 1986, a young man died of a cocaine overdose in a college dorm as his friends begged 911 operators to save his life.

In 1986, an Anti-Drug Abuse Act passed, dooming thousands of people to prison sentences, and going down as one of the most extreme and imbalanced drug acts in the history of the United States of America.

In this article, we are going to talk about Len Bias.

There are figures in history who we begin to see fade into the background, forgotten to the annals of time. We forget their names and their history, but their impact lingers, a spirit that haunts the anthropological halls of our era. The unfortunate reality is that only a select few choose who we memorialize from our past, who is deserving of biopics, statues, and social studies lessons. Often left out of such epics are those who were used. The individuals in history whose lives and deaths were fodder for some other major figure who will be written about in decades to come.

Leonard K. Bias was 22 years old when he overdosed on copious amounts of cocaine two days after being drafted to the Boston Celtics. In that same year, his death will be the central point in a campaign against drugs that will disproportionately impact marginalized communities and ruthlessly tear apart neighborhoods and families without remorse. The act catalyzing this travesty passed in 1986 and will be colloquially named “The Len Bias Law.” This very act will result in the ten-year imprisonment of Bias’ childhood friend Derrick Curry. The question remains; how do we go from NBA draft pick with chances of being one of the greatest players of all time to a devastating drug campaign we still feel the consequences of today?

Let’s first establish one thing: cocaine was not a new drug for the NBA in the 1980s. Far from it, with The Washington Post in 1980 estimating between 40% and 75% of the players in the league used the stimulant. In the same year that Bias dies, Michael Ray Richardson (also known as “Sugar”) would be banned from the NBA due to cocaine usage. The death of Bias and the banning of Richardson did not represent a sudden burst of coke usage in the NBA, it simply shone a light on the existing problem to the point that the public couldn’t ignore it. There was a culture established between cocaine use and professional basketball. This is important to consider when we think about the year or so leading up to Bias’ draft and subsequent overdose. Bias was only 22 when he passed away. We now know that the brain, on average, is still in development up until age 25, with the prefrontal cortex developing fully last. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for our ability to inhibit impulse, think ahead, and plan. Bias was already facing two major risk factors in his age and the sports culture he played in, and we haven’t even touched on race.

Race influences everything, so it would be naïve to suggest that it didn’t have a part to play here. Bias had a persona. He was a born-again Christian and a role model for children. He was an elite basketball player on track to potentially be one of the best that’s ever been. He was a 22-year-old black young adult trying to make it in 1980s America, a place where racism ran (and continues to run) rampant. The pressure placed upon him to be the representative “good” black person would have been insurmountable, any wrong step could ruin not only his career but also the “model minority” status placed upon him by media corporations and politicians. These are pressures that some of us wouldn’t be able to handle as fully developed adults, let alone when we were in college or the early workforce, trying to figure out how to be on our own for the first time. Some articles will try to push Bias’ decisions and cocaine use onto his friends’ influence, say that he was molded by the people around him. I can’t say that his peers had no impact on him, but to boil down everything that Bias struggled with, and that his extravagant and excessive lifestyle might have been a response to, just to peer pressure… That’s a disservice to the anxieties and stress he surely must have endured.

In the end, we will never know exactly why Bias did cocaine, and what the context was about that night, June 23, 1986. What we do know is that the following media campaign was a catastrophe.

As news of Bias’ death and the facts surrounding it were leaked to the press, a prevailing tale was broadcasting across the nation: American’s had a problem, and that problem was crack. Attentive readers might be a bit confused here: didn’t Bias die of cocaine overdose? Yes, he did. In spite of this, media publications and politicians decided to utilize his death in their campaign against crack, which allowed them to shift their policies from targeting predominately white communities to targeting predominately black communities. If the news were to be believed, every child and their mother were hooked on the rock. The reality, though, simply didn’t hold up to the myth of America’s “drug of choice”, with the 1999 New York Times reporting “…crack was never America’s drug of choice – it did not come close… Crack was never the epidemic it was held up to be… Although crack was labeled the world’s most addictive drug, 10 years of national surveys have shown that most people who try crack do not continue using it.”

Politicians, however, are not required to follow the facts. Case in point, let’s talk about Thomas Phillip “Tip” O’Neill Jr. Tip was the speaker of the House of Representatives, and a proud Boston-born politico. He was also facing midterm reelections in November 1986 and in need of political momentum for his party (the Democrats). In a push to win over Americans, Tip thought Democrats needed to be the face of the “tough on drugs” movement, which in turn looked like stricter sentences for drug offenses. However, the Republican party was not one to be outdone when it came to fighting the War on Drugs. This political battle manifested via increasingly emotional and exaggerated appeals, fixating on stereotypes and scare tactics. Just like how in life Bias became the figurehead for black performance in sports, in death he became the figurehead for anti-drug campaigns. Just four months after Bias’ passing, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, also known as the Len Bias Law, would be signed into effect by Ronald Reagan.

David Farber, a historian and author of War on Drugs: A History, would note the following about the act: “This bill started to become a bidding war around who could punish drug dealers and drug users more.” Rather than negotiating punishment down, the two parties were seeing who could take it further, make it worse for the punished. The result? An act that specified the amount of a drug that would result in prosecution. For a five-year sentence, crack was set at 5g, and cocaine (the actual drug that killed Bias) was set to 500g. These sentences rose to 10 years for 50g of crack and 5,000g of cocaine. Additionally, anyone who sold drugs that resulted in death or severe injury would have a minimum sentence of 20 years. This pre-determined minimum act for drugs would go on to set a precedent that other areas, such as illegal gun possession, immigration violation, identity theft, sex crimes, and fraud, would follow. Kevin Ring, vice president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums spoke on the 1986 act: “The ’86 act has caused so much damage because it ratcheted up sentences for everyone.” (There is far more to be said on the media frenzy that was the “crack epidemic” and the impact it had on the black community as a whole, but I will save that for another article.)

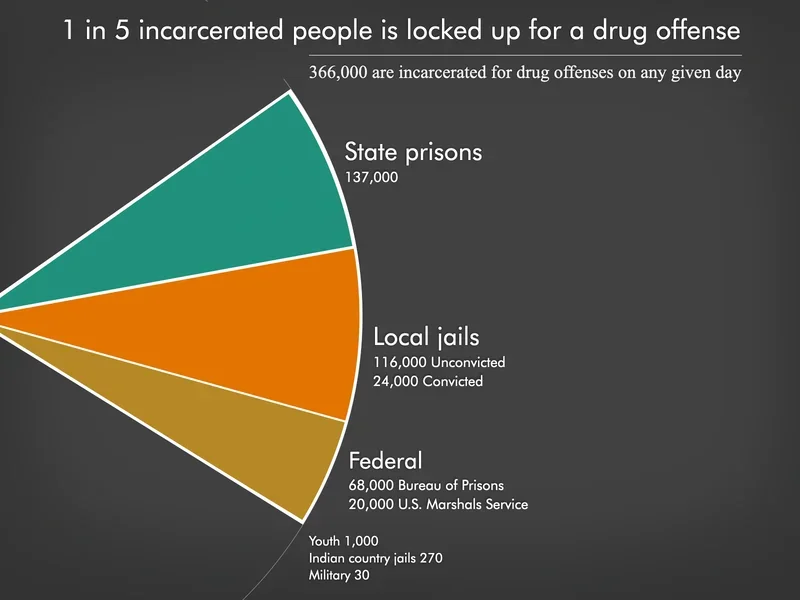

Politicians claimed that the intent of the act was not to fill United States prisons with people who use drugs, it was meant to target kingpins of the drug market. This was not the case. The mandatory minimums were far too low to target high level drug traffickers. Instead, the act allowed police and prosecutors to target street-level agents and those only involved in the peripheries of the system. We also see the act being utilized to disproportionately target black communities, despite some evidence showing that black and white individuals used crack at around the same rates. In 1985, approximately 35,000 people were in the federal prison system, with 9,500 of those people in for drug-related charges. In March of 2025, 154,155 people were in the Federal Bureau of Prisons, according to the United States Sentencing Commission, with 62,260 of those individuals being charged with drug trafficking. That number doesn’t include state prisons, U.S. Marshals Service, local jails, or tribal jails. The graph below is sourced from the Prison Policy Initiative (Sawyer and Wagner, March 11, 2025). Certain numbers functioned as estimates based on available data, with the team rounding their findings for clarity, if you would like to read more about their data sources, please refer to their article here:

Graph Sourced from Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2025).

It's important to remember these current numbers are after some of the more draconian drug trafficking punishments have been repealed as well. In 2016, there were 195,000 inmates, with 85,000 in for drug trafficking. As mentioned in the beginning of this article, one of those impacted would be Derrick Curry, a childhood friend of Bias who was arrested with a ten-year sentence for crack trafficking, even though he had no prior offenses. Curry would go on to join Families Against Mandatory Minimums where he supports their advocacy with tales of his experience.

Len Bias should never have been the story attached to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. He was an insanely talented college athlete who was struggling and suffered a tragic end. His existence has become mythologized, with think pieces written about what could have been. It’s important that we take a step back and consider the person behind it all. Even in death, we have placed expectation and blame on someone, who, in the end, was just a boy who liked basketball.

SOURCES:

Ashraf, R. (2023, June 22). Len Bias: The NBA draft star and his overdose – a death that changed America. BBC Sport. https://www.bbc.com/sport/basketball/65953921

Keyes, L., Bing, R. L., & Keyes, V. D. (2021). America’s Anti-Drug Abuse Act, the Disproportionality of Drug Laws on Blacks: A Policy Analysis. Justice Policy Journal, 18(2), 1-14. https://www.cjcj.org/media/import/documents/anti-drug_abuse_keyes_et.al.pdf

Reinarman, C. & Levine, H. G. (2004). Crack in the Rearview Mirror: Deconstructing Drug War Mythology. Social Justice, 31(1-2), 182-199). https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.ucsc.edu/dist/f/1564/files/2023/09/reinarman-2004-crack-rearview-mirror.pdf

Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2025, March 11). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2025.html#dataintro

Schuppe, J. (2016, June 19). 30 Years after Basketball Star Len Bias’ Death, Its Drug War Impact Endures. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/30-years-after-basketball- star-len-bias-death-its-drug-n593731

Weinreb, M. (N.D.) The Day Innocence Died. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/espn/eticket/story?page=bias&redirected=true